|

Last Update:

Thursday November 22, 2018

|

| [Home] |

BACKGROUND Nepal is situated on the southern slopes of the central Himalayas and occupies a total area of 147,181km2 between latitudes 26°22' and 30°27' N and longitudes 80°40' and 88°12' E. The average length of the country is 885km from east to west and the width varies from 145km to 241km, with a mean of 193km north to south. Hills and high mountains cover about 86% of the total land area and the remaining 14% are the flatlands of the Terai, which are less than 300m in height. Altitude varies from some 60m above sea level in the Terai to Mount Everest (Sagarmatha) at 8,848m, the highest point in the world (HMGN/MFSC, 2002). According to Hagen (1998), Nepal has seven physiographic zones, which are, from south to north: the Terai, Siwalik Hills zone, Mahabharat Lekh, Midlands, Himalaya, Inner Himalaya, and the Tibetan marginal mountains. The latest physiographic data shows that the total land area of Nepal comprises around 4.27 million hectares of forest (29% of total land area), 1.56 million hectares of scrubland and degraded forest (10.6%), 1.7 million hectares of grassland (12%), 3.0 million hectares of farmland (21%), and about 1.0 million hectares of uncultivated land (7%). A wide range of climatic conditions exists in Nepal mainly as a result of altitudinal variation. This is reflected in the contrasting habitats, vegetation, and fauna that exist in the country. The average annual rainfall in Nepal is about 1600mm, but total precipitation differs in each eco-climatic zone. The eastern region is wetter than the western region. In general, the average temperature decreases by 6°C for every 1,000m gain in altitude (Jha, 1992; HMGN/MFSC, 2002). Nepal’s biodiversity is a reflection of its unique geographic position and altitudinal and climatic variations. Nepal’s location in the central portion of the Himalayas places it in the transitional zone between the eastern and western Himalayas. It incorporates the Palaearctic and the Indo-Malayan biogeographical regions and the major floristic provinces of Asia (the Sino-Japanese, Indian, western and central Asiatic, Southeast Asiatic, and African Indian desert) creating a unique and rich terrestrial biodiversity (HMGN/MFSC, 2002). Nepal hosts a great diversity of wetlands, which cover approximately five percent of its total land area (DOAD, 1992). The ecological diversity of the wetland ecosystems of Nepal is very great (Scott, 1989). The country has approximately 6,000 rivers and rivulets, including permanent and seasonal rivers, streams and creeks (IUCN Nepal, 2004). The major perennial river systems that drain the country are the Mahakali, Karnali, Narayani, and Koshi Rivers, all of which originate in the Himalayas. Medium-sized rivers include the Babai, West Rapti, Bagmati, Kamla, Kankai, and Mechi; these generally originate in the Mid-hills or in the Mahabharat range. The Terai region has a large number of small and usually seasonal rivers, most of which originate in the Siwalik Hills (HMGN/ADB/FINNIDA 1988). IUCN Nepal has identified 163 wetlands in 19 Terai districts covering 724,257 hectares (Bhandari, 1998). An inventory carried out by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development and the United Nations Environment Programme listed 2,323 glacial lakes (75.70 km2) above 3,500 m. in Nepal. These include 182 lakes of 8 hectares or more, and 2,141 with areas less than 8 hectares (Mool et al., 2002). Nepal’s wetlands support significant species diversity and populations of globally threatened flora. Seventeen out of twenty endemic vertebrates found in Nepal – including eight fish and nine herpetofauna species – are wetland dependent (IUCN Nepal, 2004). A total of 182 fish species have been recorded in Nepal, including eight endemic species (Shrestha, 2001). Nepal’s wetlands are equally important for flora. Wetland-dependent flora includes the plants that flourish well in wetland habitats such as marshes, swamps, floodlands, in rivers or river banks (Chaudhary, 1998). About 25% of Nepal’s estimated 7,000 vascular plant species are wholly or partly wetland dependent. Twenty-six of the 246 angiosperm species are wetland dependent (Shrestha and Joshi, 1996). Of the 91 nationally threatened plants found in Nepal, ten are dependent on wetlands. Nepal’s wetlands hold several species of wild cultivars and wild relatives of cultivated crops. At least 318 wetland-dependent plant species have been recorded in the Terai wetlands alone. At least 254 amphibious/emergent species are found exclusively in aquatic habitats (IUCN Nepal, 2004). A total of 187 mammal species have been recorded in Nepal (Shrestha, 1997). Among these, 27 mammal species have been formally protected under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1973. Since then, the list of protected mammals has not been revised. Thirteen otter species lives in the world, five of them inhabiting Asia. Nepal holds three species, the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra), the Smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata) and the Asian small-clawed otter (Aonyx cinerea) representing 1.6% of the mammals cited in the country. There is an important lack of information on the status and ecology of otters in Nepal, and only a few preliminary studies have been conducted (Houghton, 1987; Acharya and Gurung, 1994; Thapa, 2002; Kafle, 2007; Bhandari, 2008; Joshi, 2009; Bhandari and GC, 2008; Kafle, 2008). Very few references are available in Nepal that address issues on otter conservation and research. Hodgson (1839) was the first to identify the presence of the Eurasian otter, Smooth-coated otter and Asian small-clawed otter in Nepal. Thereafter, only a few scattered otter surveys have been conducted in the country. Houghton (1987) published an article in the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin based on his survey in 1984/85 showing the common occurrence of Smooth-coated otter along the length of Narayani River within the Chitwan National Park of Nepal. Acharya and Gurung (1994) from their 1991 survey, reported on the status of Eurasian otter in the Rupa and Begnas Lakes of Pokhara valley. Thapa (2002) conducted a preliminary survey on the population status of the Smooth-coated otters in the Karnali river of Bardia National Park, and the results are available on the IOSF website (http://www.otter.org/nepal.html). The Asian Section of the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group conducted a training workshop on “Survey techniques and monitoring otter populations” for rangers and conservationists in Chitwan National Park, Nepal from 7-9 March 2006. Bhandari (2008) studied the current conservation problems and distribution of otters in the Karnali river of Bardia National Park. Outside of this protected area, some work on the status of the Smooth-coated otter was recently done (Joshi, 2009). Bhandari and GC (2008) published an article on their preliminary survey of the otter in Rupa Lake in the Journal of Wetlands Ecology. Smooth-coated otters are considered to be common in the large rivers of Nepal, particularly Narayani, Koshi, Karnali and Mahakali (Shrestha, 1997). Due to these gaps in the knowledge of otters in the region, Kafle (2008) points out the urgency of direct action for the conservation of otters in Nepal. WFN has launched the Nepal Otter Project (www.ottersnepal.org) to initiate long term monitoring and conservation of otters in Nepal in partnership with Chester Zoo and NEF. Thapa (2009) is carrying out another survey of the status, distribution and habitat use by Smooth-coated otters in the Narayani river of Nepal with funds provided by the IOSF (http://www.otter.org/project3.html). CURRENT STATUS OF OTTERS IN NEPAL Nepal is home to the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra), Smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata) and Asian small-clawed otter (Aonyx cinerea) (Hodgson 1839). Nepal holds three out of the four species of Asian otters (Figure 1).

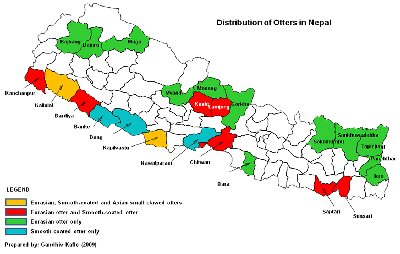

Distribution of Otters in Nepal The presence of otters has been confirmed in 24 districts of Nepal covering both lowland and hilly regions. The Eurasian otter is recorded in 8 districts in the Terai region and 13 districts in the hilly regions. The Smooth-coated otter is recorded in 10 districts in the Terai region and 2 districts in the hilly regions. All three species of otters are recorded in two lowland districts: Kailali and Kapilvastu (pers. obs); D. Gaire, (pers. com.); Shrestha, 1997; Bhandari, 1998). This shows that the Smooth-coated otter is distributed mainly in the Terai region while the Eurasian otter is distributed both in the Terai and hilly regions of Nepal. Eurasian Otter The Eurasian otter mainly lives in streams and lakes. It shelters in hollows in rocks and boulders and below the roots of trees growing in moist areas near water bodies. It has been reported as occurring as high as 3600m in Nepal (Shrestha, 1997; Prater, 1971 in Ruiz-Olmo et al., 2008). During summer (April - June) in the Himalayas they may ascend up to 3,660m. These upward movements probably coincide with the upward migration of the carp and other fish for spawning. With the advent of winter the otters come down to lower altitudes (Prater opus cit.). In most parts of its range, its occurrence is correlated with bank side vegetation, which shows the importance of vegetation to otters (Mason and Macdonald, 1986 in Ruiz-Olmo et al., 2008). Otters in different regions may depend upon differing features of the habitat, but to breed, they need holes in the riverbank, cavities among tree roots, piles of rock, wood or debris. The Eurasian otters are closely tied to a linear home range. Most of their activity is concentrated in a narrow strip on either side of the interface between water and land (Kruuk, 1995 in Ruiz-Olmo et al., 2008). Green et al., (1984) and Kruuk, 1995 in Ruiz-Olmo et al. (2008) found that adult males spent most of their time along the main rivers, whereas adult females occupied tributaries or lakes, as they do in Austria (Kranz, 1995 in Ruiz-Olmo et al., 2008). Young animals usually occupy peripheral habitat. Green and Green (1983) in Ruiz-Olmo et al. (2008) found differences between immature and mature young males, the latter having access to all available habitat and the former restricted to marginal habitat, supplemented by visits to the main river when vacant, temporally or spatially. Available presence records of Eurasian otters in Nepal come from the Annapurna Conservation Area, Makalu Barun National Park, Koshi Tappu wetland, Rara National Park, Bardia National Park, Ghodaghodi Lake Area, Saptari, Sunsari, Chitwan, Kapilvastu, Bara, Kailali, Kanchanpur, Bajhang, Bajura, Ilam, Panchther, Taplejung, Gorkha, Lamjung, Myagdi, Solukhumbu, Manang and Sankhuwasabha. Smooth-coated Otter The Smooth-coated otter selects the shores of lakes, large rivers, streams, and canals, and it even uses rice fields for foraging (Shrestha, 1997; Foster-Turley, 1992). Resting sites are commonly in burrows closely linked to the water’s edge. Sometimes the species hunts in forests as a forest carnivore. The Smooth-coated otter is essentially a ‘plains’ species (Hussain et al., 2008). In mountainous areas of Nepal animals are present up to 1500m (Shrestha, 1997). The Smooth-coated otters prefer rocky stretches since these provide sites for dens and resting places. River stretches with bank side vegetation and marshes are used in proportion to their availability especially in summer, as they provide ample cover while travelling or foraging. Open clayey and sandy banks are largely avoided as they lack cover for escape routes (Hussain 1993, Hussain and Choudhury, 1995, 1997 in Hussain et al., 2008). In rice fields and pond areas they prefer sites having a moderate diversity of vegetation. Rivers with moderate to slow or stagnant water and water bodies having a width of 10-40 m are preferred (Hussain et al., 2008). This otter is the most widely distributed species in Nepal, present at least in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Bardia National Park, Chitwan National Park, Sukla Phanta Wildlife Reserve, Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, Ghodaghodi Lake Area, Jagadishpur Reservoir, farmland in the Lumbini Area, Rani Lake in Kanchanpur, the Karnali river in Bardia, Beeshazari and associated lakes, Banke, Dang, Nawalparasi, Bardia, Kailali, Chitwan, Sunsari, Kapilvastu, Kanchanpur, Kaski, Lamjung and Saptari. Asian Small Clawed Otter The typical habitats of Asian small-clawed otter are freshwater swamps, forested rivers, meandering rivers, mangroves and tidal pools (Shrestha, 1997; Muller, 1839 in Hussain and de Silva, 2008). Like the Smooth-coated otter, the Asian small-clawed otter dislikes bare and open areas that do not offer any shelter (Melisch et al. 1996 in Hussain and de Silva, 2008). In Thailand, the rapid-flowing upper areas of the Huay Kha Khaeng were dominated by L. lutra, the slowly meandering river near the dam and the dam itself were used by L. perspicillata while the Asian small-clawed otter occurred mostly in the middle sections, but also in the upper reaches (Kruuk et al. 1994). In riverine systems it prefers moderate and low vegetation structure, though its presence was also observed on banks with poor vegetation cover. Neither in ponds nor in rice field areas did they show preference for any of the vegetation structure categories, though poor or bare structural conditions were the least favoured both in riverine and pond areas and along the rice fields (Hussain and de Silva, 2008). In Nepal, this species has been recorded up to about 1300m. Few localities are nowadays known for this otter, although it is present in Kailali and Kapilvastu. When different otter species occurred in the same site there was evidence of difference in use of the habitats. Signs of the of small-clawed otter were found wandering further away from the river than the two other species, between patches of reeds and river debris where crabs were more likely to be found (Kruuk et al., 1994) .Otters in Pokhara valley lakes, Kaski District The presence of the three otter species has been confirmed in Khola Besi, Bhangara, Talkhola and Simal Danda of the Rupa Lake area, but in this last site it has not been confirmed yet. Indeed, people from the Rupa Lake appear to have seen 33 otters over the last 12-15 years (Bhandari and GC, 2008). There was an unusual practice of hunting/killing otters in the Rupa lake area 20-25 years ago by hiring hunters from the Terai with the help of dogs. The major reason for such killing was the predation by otters on fish. Eurasian otters inhabit Rupa and Begnas Lakes, whereas the Vijaypur stream in Pokhara valley supports Smooth-coated otters (Acharya and Gurung, 1994). Otters along the Karnali River and streams, Bardia District Populations of Smooth-coated otter occur along the banks of the Grewa River, Khaura River, Batahani River, Orai River, Lamak Lake, Gola ghat area, Banjara ghat area and the Khaurahi stream in Bardia district. Based on spraint counts, Bhandari (2008), estimated that nearly 40 otters are present along the banks of Grewa River, Khaura and Batahani River in Bardia National Park within a 1.98 square kilometre area. But it is impossible to estimate otter population size, either in terms of number of individuals or relative abundance, since indices from spraint counts alone, using the number of spraints left by an otter, vary on a seasonal basis and studies evidence the lack of any relationship between the number of otters in an area, or their activity on a site, and the number of spraints found during otter surveys. However, the resulting otter density calculated from the data as interpreted by the author: 40 otters in 1.98 km2 = 20.20 otters/km2 could be correct when groups of 4-6 animals are present, but previous work on Smooth-coated otter densities record it as being a low density species, one of the lower of the world’s otters. This shows that caution should be used in interpreting an author’s work. Thapa (2002) indicated the presence of the Smooth-coated otter in Damakantar, Banka, Bung ghat, Lalmati area, Danpur area, Gola ghat area and the Khaurahi stream in Bardia National Park; and estimated one Smooth-coated otter per km of river in a 35-km stretch of the Geruwa River in Bardia National Park. The data was from direct observations taken at different time and space intervals - not at the same time - along the whole of the study area. The observations were independent and likely to overestimate the real size, or to underestimate the real size if a part of the population was misidentified. The Orai River in Bardia is a potential habitat for otters (Joshi, 2009). Otters in the Narayani River, Chitwan District The Smooth-coated otter is believed to be common along the Narayani River within the Chitwan National Park of Nepal (Houghton, 1987). The significant number of signs in this area could indicate in some way the existence of a reasonable otter population in the area. Otters in the Ghodaghodi Lake Area, Kailali Kafle (2007) recorded the presence of Eurasian otter and Smooth-coated otter in the Ghodaghodi Lake area of Kailali district through interviews with a key informant. MAJOR FACTORS PUTTING OTTERS AT RISK IN NEPAL There is very little, and scattered, information from Asia on otters. It suggests that in many countries of Asia, there have been declines in numbers and reduction of ranges, and concern is expressed about the conservation of the species in many parts of the continent (Foster-Turley and Santiapillai, 1990; De Silva 1995; Conroy et al., 1998). Like most Lutra species, fish is the major prey of Eurasian otters sometimes exceeding more than 80% of their diet (Erlinge, 1969; Webb, 1975; Ruiz-Olmo and Palazon, 1997 in Ruiz-Olmo et al., 2008). The range of fish in the diet of Smooth-coated otters varies from 75% to 100% (Tiler et al., 1989; Foster-Turley, 1992; Hussain, 1993; Melisch et al., 1996; Hussain and Choudhury, 1998 in Hussain et al., 2008). The Small clawed otter feeds mainly on crabs, snails and other molluscs, insects and small fish such as gouramis and catfish (Pocock, 1941; Wayre, 1978 in Hussain and de Silva, 2008). They supplement their diet with rodents, snakes and amphibians as well (Hussain and de Silva, 2008). The otters supplement their diets with shrimp/crayfish, crab and insects, and other vertebrates such as frog, mudskippers, birds and rats. Any activities adversely affecting the diversity and population of fish and aquatic organisms can have enormous effects on otter populations in Nepal. Moreover, the degradation of wetland habitat can directly affect otter survival and reproduction. The aquatic habitats of Nepal are also vulnerable to human activities. The major factors putting Nepalese otter populations at risk are as follows: Water Pollution and Loss of Prey: Discharges from the Gorkha Brewery and the Bhrikuti Paper and Pulp factory are the major source of pollution in the Narayani River. Due to comparatively high number of industries in the lowland Terai, many rivers and streams there are polluted by industrial waste. Different chemicals such as Phoret, Thiodan, Methyl parathion, Cypermethrin, Dieldrin, Aldrin, Endrin and chemical fertilisers are increasingly used by farmers to increase crop production. These toxins run off into water bodies to be absorbed by aquatic fauna. These pesticides are also used for poisoning birds (both to prevent crop predation and for use as food) and in fishing bait. Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS), a disease caused by the fungus Aphanomyces invadans in the internal tissue of fish has been reported in Nepal since 1983. The deterioration of water quality in water bodies provides favourable environmental conditions for the growth of A. invadans in fish. Over 40 species of fish, mostly freshwater species, are reportedly susceptible to EUS with Catfish (Wallago attu and Mystus spp.), Snakeheads (Channa spp.) and Barbs (Puntius spp.) being the most susceptible. EUS has been reported in the Koshi Tappu wetland area since 1983, where it has caused high mortality of native fish, and from Ghodaghodi Lake since 1998 (IUCN Nepal, 2004). The number of fish species in the Bagmati River has declined from 54 to 7 within a decade as a result of the inflow of industrial sewage. The high concentration of organic matter and chemicals in effluents has killed fish and destroyed the plant life they depend on (Shrestha et al., 1979; Sharma and Pantha, 1992). In Pokhara, water pollution and solid waste disposal problems have been greatly exacerbated by the establishment of tourist facilities along the shores of Phewa and Begnas lakes, and their water quality has deteriorated due to faecal contamination from the direct discharge of sewage via drains, including the overflow from septic tanks in hotels and restaurants. Washing of clothes by hotels, restaurants and households results in the discharge of over 100kg of soap and detergents daily into Phewa Lake (Oli, 1997). The contamination of freshwater ecosystems with harmful chemicals can put otters at risk due to the adverse effects on their physiology. EUS can decrease the diversity and population of fish species thus affecting the dietary diversity of otters. Hunting and Killing: There are records of killing of otters for their pelt, meat and for the uterus that is thought to have medicinal value, but the effects of hunting on their populations remains unknown (IUCN Nepal 2004). Fishpond owners consider otters as a threat to fish farming as otters eat fish in their ponds at night. In Rupa Lake in the Pokhara valley in Nepal, otters used to be hunted by using dogs and specially trained hunters from India to prevent damage to fish populations – in private ponds and natural lake areas in the 1980s-90s. In 2004, one otter was killed by local people chasing it for the same reason (Author's pers. obs.). Loss of Wetland Habitat: Lack of clear demarcation of wetland boundaries has increased wetland loss and degradation in Nepal. Encroachment on wetlands is primarily due to: (i) drainage for irrigation, reclamation, and fishing; (ii) filling-in for solid waste disposal, road construction and commercial, residential, and industrial development; (iii) conversion of sites for aquaculture; (iv) construction of dams, barrages, and other barriers to control water flow; (v) groundwater extraction using high-powered pumps, and digging ditches in sites where there is no inflow of water; (vi) discharge of sediments and pollutants from nearby areas; (vii) grazing; and (viii) removal of soil from the site (HMGN/MFSC, 2002). The lake shores in the Pokhara valley are being encroached for agricultural conversion (pers. obs.). This encroachment has resulted in a number of negative impacts, including reduction of wetland areas, deposition of silt and sediment, and eutrophication caused by agricultural runoff and/or industrial effluents. Construction of barrages in the Karnali and Narayani rivers lead to major changes in seasonal water availability, temperature regimes, water energy, bed and suspended material transport and oxygenation of the rivers themselves, as well as in associated vegetation and faunal communities. It has affected the breeding behaviour of a number of fish species and also the fish population (IUCN Nepal, 2008). Sedimentation is also one of the major problems in the lakes of Nepal, reducing the lake size and changing the water discharge pattern (pers. obs.). These activities and processes have degraded the wetland habitat for otters. Limited research and awareness: Most of the research and conservation efforts have been concentrated on large mammals within the protected areas. Several mammals including otters do not have priority in research and monitoring programmes either inside or outside the protected areas of Nepal. The degree of understanding among people, both the general public and wetland dwellers, is too low, given that many of them are unaware of the existence of otters (pers. obs.). RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION IMPLICATIONS Nepal supports 3 out of 5 of Asia’s otter species, out of a total of 13 worldwise. This highlights the global importance of conserving otters in Nepal. However, the status of otters in Nepal has not been explored enough yet. Few studies have been carried out in the lowland Terai of Nepal on distribution, population of, and threats to otters. No intensive studies on otters have been carried out in the wetlands of all the ecological zones of Nepal. The following recommendations have been made for research and conservation of otters in Nepal: Research on Basic Ecology of Otters: The analysis shows that a preliminary status survey of otters has only been conducted in Kaski, Bardia and Chitwan districts, and only on some freshwater sites. Where presence/absence information on otters is available, intensive research focusing on the basic ecology of otters should be initiated. The wetlands in the Terai region of Nepal are the potential sites to initiate ecological research, as presence/absence information on otters is more available in this region than in the other ecological zones of Nepal. However, there are additional wetland sites in the Terai where presence/absence information is not available. National Otter Survey: Nepal has 75 districts and the presence of otters has been confirmed in only 24 districts. In the other districts, surveys have not been carried out, so information on occurrence (presence/absence) of otters is generally unavailable. The presence/absence information on otters in several sites was documented decades ago based on participatory approaches, usually interviews with key informants. These gaps in knowledge emphasize the urgent need for a systematic field-based survey for otters, focusing on three ecological zones: the Terai, Hills and Mountains of Nepal. Most of the information on the presence/absence of otters came from the protected areas and Ramsar sites of Nepal, which have conservation priority. Insufficient studies on freshwater ecosystems outside the protected areas highlight the information gap on the presence/absence data for otters. Based on the distribution range of the otters in South Asia and Nepal, it is possible that otters are present in additional districts of Nepal. Rupandehi district lies between Nawalparasi and Kapilvastu districts (the sites with otters), and is a potential site for occurrence of the Smooth-coated otter due to similar climatic and topographical conditions – hence priority sites for further study. Similar projection can be applied to Parsa, Rautahat, Sarlahi, Mahottari, Dhanusa, Siraha and Morang districts in eastern Nepal, which join the protected areas network with similar climatic and topographical conditions. The Middle Hills region has few protected areas in comparison to the lowland Terai and high mountain regions of Nepal. Information on wetlands distribution in the Middle Hills region is not available. In this context, the information on otters is very scanty except in the Pokhara valley. Considering the altitudinal range of distribution of the Eurasian otter in Nepal, it is highly possible that additional Middle Hill districts have freshwater ecosystems with otters. At least Dhading, Tanahun, Baglung, Parbat, Makawanpur, Jhapa and Dhankuta ,which border the sites with known presence of otters in the Middle Hills region, can be priority sites for preliminary assessment of otter presence/absence. In the initial stage, focus should be given to participatory approaches to collecting presence/absence information on otters. In-depth interviews with older people, fishermen and those living near wetlands can be the starting point for this. The basic information on presence/absence of otters can then be used for designing and implementing intensive research programmes. It will also be a starting point for identifying Important Otter Areas or Hotspots in Nepal. Integrated Wetland Management and Capacity Building: Wherever otters are present, some sort of conflict exists between fish farmers and otters due to fish predation by otters. Wetlands in Nepal are negatively affected by human activities, and these threats have the potential to directly impact the survival of otters. The vast majority of Nepalese people know nothing of the existence of otters in the world in general and Nepal in particular. For these reasons, management programmes using otters as a key indicator species, that consider all the ecological aspects of these animals (i.e., habitat and diet preferences, importance in the ecosystems and conservation problems) can be very valuable to the people living in the vicinity of wetland habitats. These kinds of programmes can increase knowledge within the local community and fish farm owners about the existence and importance of otters, perhaps helping to reduce the antagonism against otters in Nepal. Otter survey components should be integrated within the conservation and management plans of wetlands. Integrated programmes on basin management can simultaneously reduce the threats to wetlands and, obviously, to otters as well. Good educational material can be a useful resource for the well-trained teacher. Educational materials with an otter conservation message can help the general public to understand otter issues and importance so that they can gradually consider the otters as an integral part of freshwater ecosystems. Educational materials such as posters, information sheets and an otter booklet in the Nepali language should be prepared and distributed to the general public with appropriate guidance to increase their understanding of otter conservation in Nepal. As the quality of information from research will depend on the knowledge and skill of the researchers, some sort of capacity building programmes, such as training, needs to be initiated in Nepal to build up interest on otter related issues. CONCLUSION Now is the time to begin these initiatives if we want to achieve otter conservation in Nepal. If timely intervention is not done, it is likely that otters will be on the verge of extinction in the country. REFERENCES Acharya, P. M., Gurung, J. B. (1994). A report on

the status of common otter (Lutra lutra) in Rupa and Begnas

Tal, Pokhara valley. TigerPaper, Vol XXI, No. 2: 21-22. Résumé : Bilan des

Recherches et de la Conservation des Loutres au Népal Resumen: Una Revision de

la Investigacion y la Conservacion de las Nutrias en Nepal |

| [Copyright © 2006 - 2050 IUCN/SSC OSG] | [Home] | [Contact Us] |